Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Renoir came from a poor Parisian family - his father was a tailor, his mother a seamstress - and by the age of thirteen he was at work in a factory, painting decorations on to china and porcelain. Undoubtedly the use of clear, light colours in this work was a permanent influence on him.

The encouragement of Monet, and the resilience of his own cheerful nature, sustained Renoir through periods of appalling poverty. He seems to have endured all his hardships with optimism, and his paintings reveal none of the problems of his life. Groups of people in riverside landscapes, dance-halls and cafes, and latterly nudes, were his principal subjects, and their warmth and charm have made him one of the best-loved of all the Impressionists.

A landscape with figures, from Renoir’s purest Impressionist period.

Reminiscent of Monet’s Wild Poppies, it was probably painted during one of the

summers that two artists spent together at Argenteuil.

A landscape with figures, from Renoir’s purest Impressionist period.

Reminiscent of Monet’s Wild Poppies, it was probably painted during one of the

summers that two artists spent together at Argenteuil.

With the arrival of the railway, the banks of the Seine beyond Paris became a popular resort for city workers. La Grenouillère at Croissy-sur-Seine was a restaurant built from several boats roped together, providing a dance floor in the evenings. This was the destination of Renoir and Money one day in 1869, when the two young friends set up their easels together en plein air and initiated the breakthrough to Impressionism.

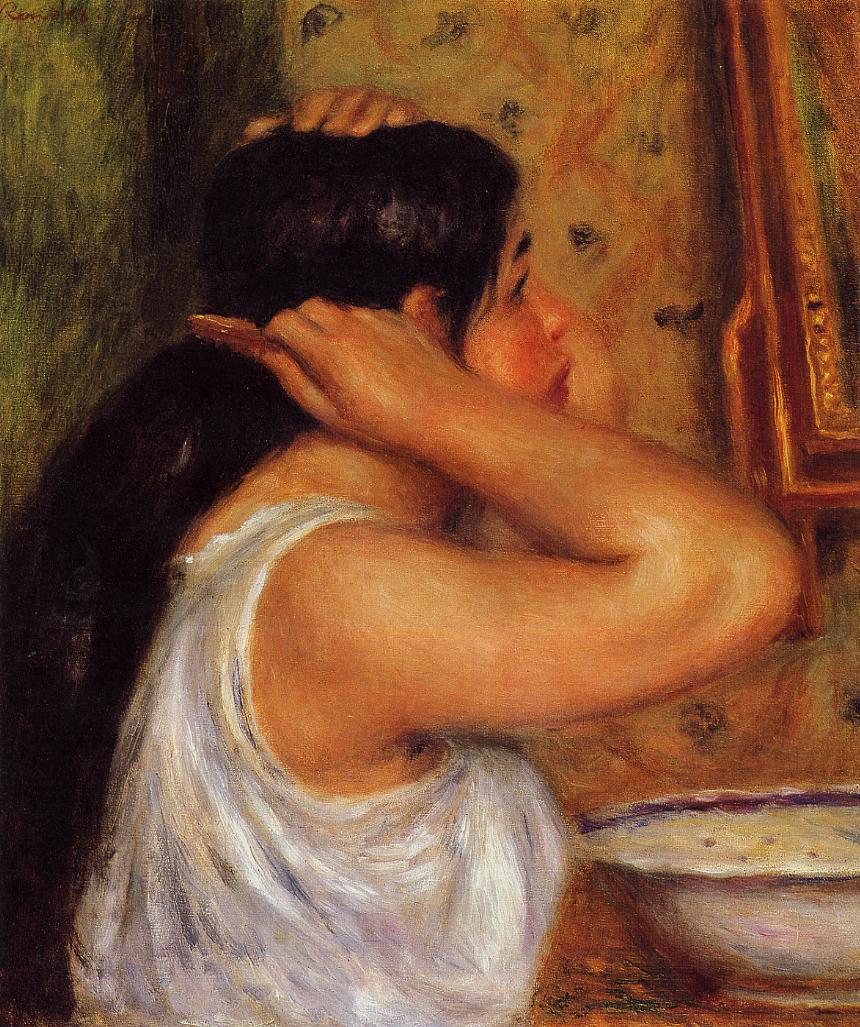

By 1881, the year he turned forty and began travelling around Europe and North Africa, Renoir knew it was time for a reassessment. He decided that colour was to be the servant, not the master, and that he would attempt to express form more carefully by tonal relationships. Not that he altered his palette; Renoir kept to the bright colours he had always favoured. In his later works, Renoir’s experimentation brought an outpouring of monumental nudes and sensual young women with luminescent skin.

The attraction of Le Moulin de la Galette is largely the result of Renoir’s

preoccupation with a technical problem: the portrayal of dappled sunlight

filtering through trees and illuminating the dancing, chattering figures

underneath, and he has mastered it with a wonderful delicacy.

The attraction of Le Moulin de la Galette is largely the result of Renoir’s

preoccupation with a technical problem: the portrayal of dappled sunlight

filtering through trees and illuminating the dancing, chattering figures

underneath, and he has mastered it with a wonderful delicacy.

He was fascinated by the pearly tints of female flesh, and frequently used this colour scheme of pinks and blues to accentuate the softness and clarity of skin tones. The play of light and shade on the girls’ dresses and hair, and on the men’s straw hats and dark jackets, softens the outlines of the figures and blends them with their surroundings and the shadows on the ground, so that a haze of diff used colour fills the entire canvas.

This cafe in Montmartre, housed in an old windmill, was a favourite gathering

place for flirting, drinking grenadine, eating the galettes or pancakes from

canvas there every week, and painted the picture on the spot. His friends and

regular models posed for most of the figures. He has captured delightfully the

atmosphere of gentle gaiety and the soft shimmering effects of summer afternoon

light.

This cafe in Montmartre, housed in an old windmill, was a favourite gathering

place for flirting, drinking grenadine, eating the galettes or pancakes from

canvas there every week, and painted the picture on the spot. His friends and

regular models posed for most of the figures. He has captured delightfully the

atmosphere of gentle gaiety and the soft shimmering effects of summer afternoon

light.

Gabrielle Renard was a distant cousin who came as his son Jean’s nurse, and stayed on as housekeeper and model for Renoir. When arthritis reduced his hands to claws, Gabrielle wrapped them in powdered gauze to prevent the skin adhering. Disabled as his father was, Claude Renoir recalled slipping paintbrushes between his father’s fingers to enable him to paint.