Claude Monet

It was from one of Claude Monet’s paintings — Impression , Sunrise — that the Impressionist group, of which he was the leader, acquired its name.

He was born in Paris, but spent most of his working life on the Normandy coast or in the French countryside, and he passionately loved the sea and the open air. Poverty dogged him for many years, and the dreary problems of how to live exasperated and depressed him. He was reduced to scrounging from his friends and patrons just to survive, and frequently had to sacrifice finished work by scraping off the paint in order to use the canvas again.

He spent the summer of 1866 at Ville d’Avray, near Paris, and it was there that

he painted Women in the Garden. He worked, as usual, out of doors, and had a

trench dug in the garden into which his huge canvas — about

eight-and-a-half feet by six-and-a-half feet — was lowered, and a pulley

arrangement was rigged up so that he could reach the top. Light interested him

more than anything, and he was concerned to reveal the fact that colour only

exists in terms of light, and that it changes in all the normal variations of

daylight and shadow.

He spent the summer of 1866 at Ville d’Avray, near Paris, and it was there that

he painted Women in the Garden. He worked, as usual, out of doors, and had a

trench dug in the garden into which his huge canvas — about

eight-and-a-half feet by six-and-a-half feet — was lowered, and a pulley

arrangement was rigged up so that he could reach the top. Light interested him

more than anything, and he was concerned to reveal the fact that colour only

exists in terms of light, and that it changes in all the normal variations of

daylight and shadow.

The scene in the garden is a study of the effects of sunlight filtering through leaves, casting dark shadows and dappling the figures of the four women (who were all modelled by Monet’s mistress Camille). Roses are in bloom, the trees are dense with the dark green leaves of mid-summer, and the women wear pale delicate dresses of embroidered cotton and fine muslin. The seated woman shields her face from the sun with a parasol; and Monet has caught precisely the effect of shade-on the colour of her skin and the top of her dress, contrasting it with the bright reflected light on her skirt and the flowers in her lap. The two women standing together are in the shade of a tree, with the sun flickering through and forming patches of light on their dresses. The fourth is in the full sun, its strong rays shining directly on to the back of her dress and her gleaming red hair. The long dark shadow in the foreground accentuates the brilliance of the light, especially where it edges the white skirts spread in a circle over the grass. The swirling movement of light summer dresses makes an extremely romantic composition, and Monet’s understanding of the effects of light bring out all its subtle variations of colour and atmosphere.

He is generally considered to be the greatest of all the Impressionist painters. He had an astonishing ability to observe and record a scene with a fresh eye, as free as possible from influences and conventions, and to paint exactly what lay before him as if he were seeing for the first time.

One of a series of twelve railway station pictures, created at different times

of the day. For his most ambitious study of the urban landscape, Monet chose

Saint-Lazare, gateway to his beloved Normandy. He concentrated on the

full-spectrum effects of light, smoke and steam, building cloud shapes with

curly brushstrokes. Monet was a master at adapting strokes to show how light

affects texture and form.

One of a series of twelve railway station pictures, created at different times

of the day. For his most ambitious study of the urban landscape, Monet chose

Saint-Lazare, gateway to his beloved Normandy. He concentrated on the

full-spectrum effects of light, smoke and steam, building cloud shapes with

curly brushstrokes. Monet was a master at adapting strokes to show how light

affects texture and form.

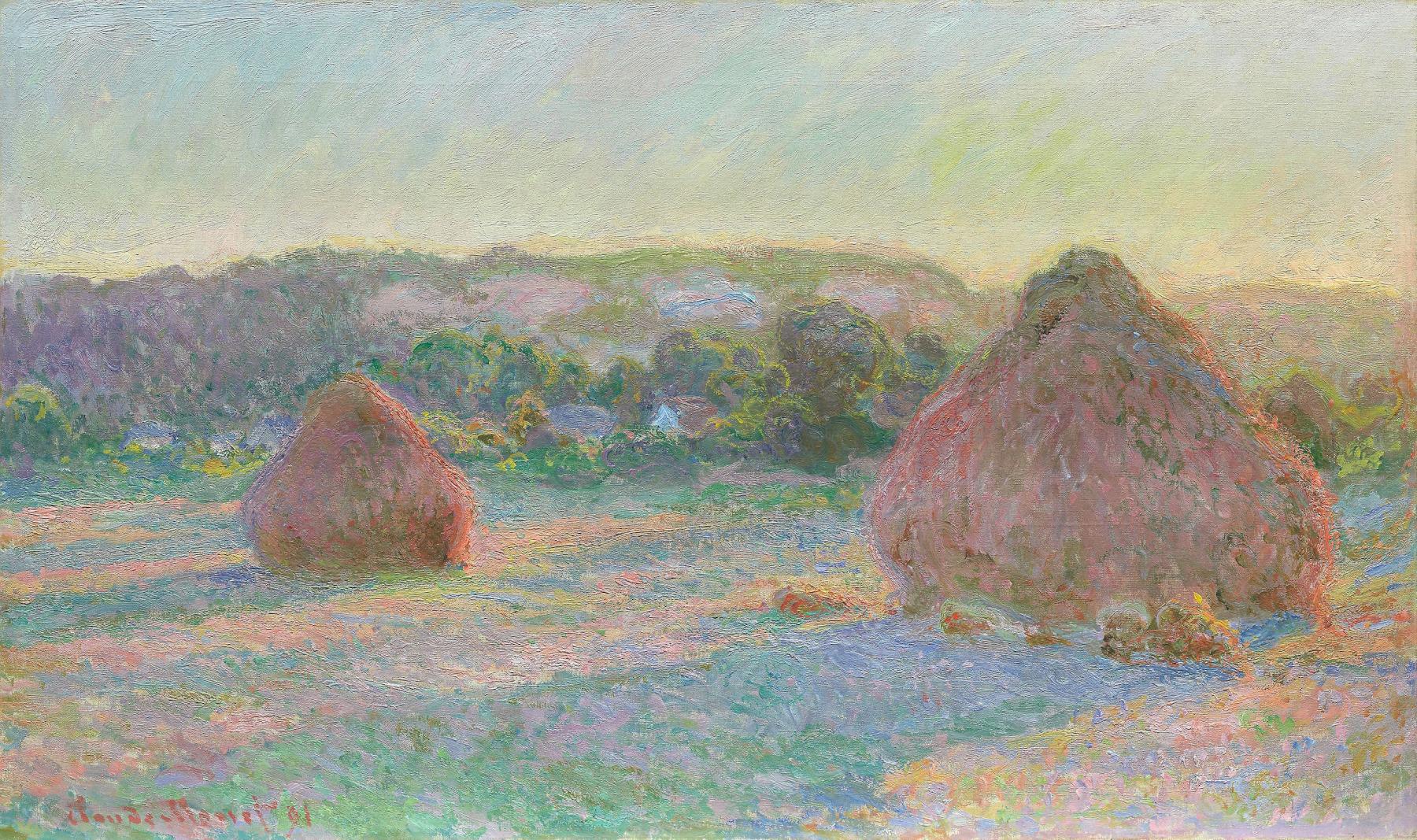

After La Gare Saint-Lazare, Monet subsequently embarked on other series

— haystacks, Rouen cathedral and the waterlilies at Giverny — each

a painstaking demonstration that atmospheric colour, caused by changes in the

light, can modulate a subject through the entire spectrum.

After La Gare Saint-Lazare, Monet subsequently embarked on other series

— haystacks, Rouen cathedral and the waterlilies at Giverny — each

a painstaking demonstration that atmospheric colour, caused by changes in the

light, can modulate a subject through the entire spectrum.

In spite of his destitute state, he more than anyone stuck to the ideals of Impressionism throughout his long life without deviating, and he was a great source of stimulation to others in the group in the face of poverty and endless criticism. Renoir said of him, ‘Without Monet, without my dear Monet who gave us all courage, we would have given up.’ After about thirty years of struggle, their work began to be understood and appreciated ; and finally it has come to be valued as one of the most important movements, and certainly the most popular, of the nineteenth century.