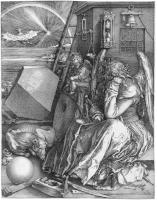

Albrecht Dürer

Dürer was born in Nuremburg, the son of a goldsmith, and he received early training in the art of drawing from his father. His first self-portrait, drawn when he was thirteen, reveals his precocious genius; its self-analysis is remarkable. Success came early, for by his twenties he was renowned throughout Europe and acknowledged as Germany’s leading artist. Vasari tells us that ‘the entire world was astonished by his mastery’. Dürer’s output was enormous, and many of his meticulously detailed woodcuts and drawings — The Praying Hands, The Young Hare — are known universally. His genius lay mainly in his draughtsmanship, and he has been described as ‘the greatest mind that ever expressed itself in line’.

From 1490-94 he travelled widely, and after his marriage made his first major trip to Italy. He was the first important German artist to do so; and it was largely through him that the academic ideas and artistic achievements of the Italian Renaissance were introduced to the North.

In this half-length self-portrait, painted when he was twenty-six, Dürer has

portrayed himself as a perfect example of the Renaissance ‘universal man’. Not

only is this one of the first self-portraits in Northern European art in which

the artist is shown in an individual study rather than as part of a group, but

it also makes a bid for the status of the artist as gentleman. (The profession

of painter at that time ranked fairly low in the social scale.) Dürer’s success

had made him a rich man ; and here his hair is elaborately curled, his clothes

are fine, and his hands immaculately gloved in grey kid. A cloak is draped

round his shoulders with a casual, stylish air, and over his shirt of bleached

and gathered linen, trimmed with gold brocade, is an elegant white doublet

edged in black, with separate oversleeves and a dashing tasselled cap. The

serious intelligence of his character can be seen in his dispassionate

objective gaze. The snow-covered mountains through the window are reminiscent

perhaps of Dürer’s travels across the Alps.

In this half-length self-portrait, painted when he was twenty-six, Dürer has

portrayed himself as a perfect example of the Renaissance ‘universal man’. Not

only is this one of the first self-portraits in Northern European art in which

the artist is shown in an individual study rather than as part of a group, but

it also makes a bid for the status of the artist as gentleman. (The profession

of painter at that time ranked fairly low in the social scale.) Dürer’s success

had made him a rich man ; and here his hair is elaborately curled, his clothes

are fine, and his hands immaculately gloved in grey kid. A cloak is draped

round his shoulders with a casual, stylish air, and over his shirt of bleached

and gathered linen, trimmed with gold brocade, is an elegant white doublet

edged in black, with separate oversleeves and a dashing tasselled cap. The

serious intelligence of his character can be seen in his dispassionate

objective gaze. The snow-covered mountains through the window are reminiscent

perhaps of Dürer’s travels across the Alps.

It is a portrait of self-scrutiny, maybe even self-promotion, and it embodies a great deal of the artist’s character and attitudes as well as his genius as a draughtsman.

Dürer realized that prints made his art available to the widest possible public

and hired an agent to sell them in the fairs and markets of Europe. The

Apocalypse was Dürer’s earliest major series, illustrating the Book of

Revelation with the Scripture on the reverse. His interpretation of the four

horsemen — War, Famine, Pestilence and Death — has never been

surpassed.

Dürer realized that prints made his art available to the widest possible public

and hired an agent to sell them in the fairs and markets of Europe. The

Apocalypse was Dürer’s earliest major series, illustrating the Book of

Revelation with the Scripture on the reverse. His interpretation of the four

horsemen — War, Famine, Pestilence and Death — has never been

surpassed.

The Four Horsemen are riding their steeds and treading on a gathering of hapless humans. An angel watches over the landscape, which is framed by majestic clouds and beams of light. The three horsemen are recognized in the Scripture primarily by the colors of their horses.

Dürer, forced to work in gray-scale owing to the limitations of the woodcut technique, clearly portrays their weaponry — trident, sword, a set of scales, and a bow — as defining features. Death is also identified as an old weary figure with a beard riding a malnourished stallion.

As the final character to join the stage, Death carries Hades with him, shown as a wide-mouthed creature swallowing a person wearing a priest’s collar and hat. The priests and nobles, like the majority of the population, are decimated by the Apocalypse. Their modern attire allows the 16th-century observer to easily envisage their own misery ahead. By covering practically the whole panel with careful detailing, Dürer wonderfully conveys the terror and turmoil of the end times.